Brief Neuropsychological Cognitive Examination Pdf Editor

The (BNCE™) Brief Neuropsychological Cognitive Examination™, published by WPS for clinicians, educators and researchers, can be purchased online.

Disability determination is based in part on signs and symptoms of a disease, illness, or impairment. When physical symptoms are the presenting complaint, identification of signs and symptoms of illnesses are relatively concrete and easily obtained through a general medical exam. However, documentation or concrete evidence of cognitive or functional impairments, as may be claimed by many applying for disability, is more difficult to obtain. Psychological testing may help inform the evaluation of an individual’s functional capacity, particularly within the domain of cognitive functioning.

The term cognitive functioning encompasses a variety of skills and abilities, including intellectual capacity, attention and concentration, processing speed, language and communication, visual-spatial abilities, and memory. Sensorimotor and psychomotor functioning are often measured alongside neurocognitive functioning in order to clarify the brain basis of certain cognitive impairments, and are therefore considered as one of the domains that may be included within a neuropsychological or neurocognitive evaluation. These skills and abilities cannot be evaluated in any detail without formal standardized psychometric assessment. This chapter examines cognitive testing, which relies on measures of task performance to assess cognitive functioning and establish the severity of cognitive impairments. As discussed in detail in, a determination of disability requires both a medically determinable impairment and As documented in Chapters 1 and 2, 57 percent of claims fall under mental disorders other than intellectual disability and/or connective tissue disorders.

Evidence of functional limitations that affect an individual’s ability to work. A medically determinable impairment must be substantiated by symptoms, signs, and laboratory findings (the so-called Paragraph A criteria) and the degree of functional limitations imposed by the impairment must be assessed in four broad areas: activities of daily living; social functioning; concentration, persistence, or pace; and episodes of decompensation (the so-called Paragraph B criteria). However, as discussed in, the U.S. Social Security Administration (SSA) is in the process of altering the functional domains, through a Notice of Proposed Rulemaking published in 2010. The proposed functional domains—understand, remember, and apply information; interact with others; concentrate, persist, and maintain pace; and manage oneself—increase focus on the relation of functioning to the work setting; because of SSA’s move in this direction, the committee examines the relevance of psychological testing in terms of these proposed functional domains. As will be discussed below, cognitive testing may prove beneficial to the assessment of each of these requirements. In contrast to testing that relies on self-report, as outlined in the preceding chapter, evaluating cognitive functioning relies on measures of task performance to establish the severity of cognitive impairments.

Such tests are commonly used in clinical neuropsychological evaluations in which the goal is to identify a patient’s pattern of strengths and weaknesses across a variety of cognitive domains. These performance-based measures are standardized instruments with population-based normative data that allow the examiner to compare an individual’s performance with an appropriate comparison group (e.g., those of the same age group, sex, education level, and/or race/ethnicity). Cognitive testing is the primary way to establish severity of cognitive impairment and is therefore a necessary component in a neuropsychological assessment.

Clinical interviews alone are not sufficient to establish the severity of cognitive impairments, for two reasons: (1) patients are known to be poor reporters of their own cognitive functioning (Edmonds et al., 2014; Farias et al., 2005; Moritz et al., 2004; Schacter, 1990) and (2) clinicians relying solely on clinical interviews in the absence of neuropsychological test results are known to be poor judges of patients’ cognitive functioning (Moritz et al., 2004). There is a long history of Public comments are currently under review and a final rule has yet to be published as of the publication of this report. Neuropsychological research linking specific cognitive impairments with specific brain lesion locations, and before the advent of neuroimaging, neuropsychological evaluation was the primary way to localize brain lesions; even today, neuropsychological evaluation is critical for identifying brain-related impairments that neuroimaging cannot identify (Lezak et al., 2012). In the context of the SSA disability determination process, cognitive testing for claimants alleging cognitive impairments could be helpful in establishing a medically determinable impairment, functional limitations, and/or residual functional capacity. The use of standardized psychological and neuropsychological measures to assess residual cognitive functioning in individuals applying for disability will increase the credibility, reliability, and validity of determinations on the basis of these claims.

A typical psychological or neuropsychological evaluation is multifaceted and may include cognitive and non-cognitive assessment tools. Evaluations typically consist of a (1) clinical interview, (2) administration of standardized cognitive or non-cognitive psychological tests, and (3) professional time for interpretation and integration of data.

Some neuropsychological tests are computer administered, but the majority of tests in use today are paper-and-pencil tests. The length of an evaluation will vary depending on the purpose of the evaluation and, more specifically, the type or degree of psychological and/or cognitive impairments that need to be evaluated. A national professional survey of 1,658 neuropsychologists from the membership of American Academy of Clinical Neuropsychology (AACN), Division 40 of American Psychological Association (APA), and the National Academy of Neuropsychologists (NAN) indicated that a typical neuropsychological evaluation takes approximately 6 hours, with a range from 0.5 to 25 hours (Sweet et al., 2011). The survey also identified a number of reasons for why the duration of an evaluation varies, including reason for referral, the type or degree of psychological and/ or cognitive impairments, or factors specific to the individual. The most important aspect of administration of cognitive and neuropsychological tests is selection of the appropriate tests to be administered. That is, selection of measures is dependent on examination of the normative data collected with each measure and consideration of the population on which the test was normed.

Normative data are typically gathered on generally healthy individuals who are free from significant cognitive impairments, developmental disorders, or neurological illnesses that could compromise cognitive skills. Data are generally gathered on samples that reflect the broad demographic characteristics of the United States including factors such as age, gender, and educational status. There are some measures that also provide specific comparison data on the basis of race and ethnicity. As discussed in detail in, as part of the development of any psychometrically sound measure, explicit methods and procedures by which. Tasks should be administered are determined and clearly spelled out. All examiners use such methods and procedures during the process of collecting the normative data, and such procedures normally should be used in any other administration.

Typical standardized administration procedures or expectations include (1) a quiet, relatively distraction-free environment; (2) precise reading of scripted instructions; and (3) provision of necessary tools or stimuli. Use of standardized administration procedures enables application of normative data to the individual being evaluated (Lezak et al., 2012).

Without standardized administration, the individual’s performance may not accurately reflect his or her ability. An individual’s abilities may be overestimated if the examiner provides additional information or guidance than what is outlined in the test administration manual. Conversely, a claimant’s abilities may be underestimated if appropriate instructions, examples, or prompts are not presented. Cognitive Testing in Disability Evaluation To receive benefits, claimants must have a medically determinable physical or mental impairment, which SSA defines as. An impairment that results from anatomical, physiological, or psychological abnormalities which can be shown by medically acceptable clinical and laboratory diagnostic techniques and must be established by medical evidence consisting of signs, symptoms, and laboratory findings—not only by the individual’s statement of symptoms. (SSA, n.d.-b) To qualify at Step 3 in the disability evaluation process (as discussed in ), there must be medical evidence that substantiates the existence of an impairment and associated functional limitations that meet or equal the medical criteria codified in SSA’s Listings of Impairments. If an adult applicant’s impairments do not meet or equal the medical listing, residual functional capacity—the most a claimant can still do despite his or her limitations—is assessed; this includes whether the applicant has the capacity for past work (Step 4) or any work in the national economy (Step 5).

For child applicants, once there has been identification of a medical impairment, documentation of a “marked and severe functional limitation relative to typically developing peers” is required. Cognitive testing is valuable in both child and adult assessments in determining the existence of a medically determinable impairment and evaluating associated functional impairments and residual functional capacity. Cognitive impairments may be the result of intrinsic factors (e.g., neurodevelopmental disorders, genetic factors) or be acquired through injury or illness (e.g., traumatic brain injury, stroke, neurological conditions) and may occur at any stage of life.

Functional limitations in cognitive domains. May also result from other mental or physical disorders, such as bipolar disorder, depression, schizophrenia, psychosis, or multiple sclerosis (Etkin et al., 2013; Rao, 1986). Cognitive Domains Relevant to SSA SSA currently assesses mental residual functional capacity by evaluating 20 abilities in four general areas: understanding and memory, sustained concentration and persistence, social interaction, and adaptation (see Form SSA-4734-F4-SUP: Mental Residual Functional Capacity MRFC Assessment).

Through this assessment, a claimant’s ability to sustain activities that require such abilities over a normal workday or workweek is determined. In 2009, SSA’s Occupational Information Development Advisory Panel (OIDAP) created its Mental Cognitive Subcommittee “to review mental abilities that can be impaired by illness or injury, and thereby impede a person’s ability to do work” (OIDAP, 2009, p. In their report, the subcommittee recommended that the conceptual model of psychological abilities required for work, as currently used by SSA through the MRFC assessment, be revised to redress shortcomings and be based on scientific evidence.

There are numerous performance-based tests that can be used to assess an individual’s level of functioning within each domain identified below for both adults and children. It was beyond the scope of this committee and report to identify and describe each available standardized measure; thus, only a few commonly used tests are provided as examples for each domain. The choice of examples should not be seen as an attempt by the committee to identify or prescribe tests that should be used to assess these domains within the context of disability determinations. Rather, the committee believed that it was more appropriate to identify the most relevant domains of cognitive functioning and that it remains in the purview of the appropriately qualified psychological/neuropsychological evaluator to select the most appropriate measure for use in specific evaluations. For a more comprehensive list and review of cognitive tests, readers are referred to the comprehensive textbooks, Neuropsychological Assessment (Lezak et al., 2012) or A Compendium of Neuropsychological Tests (Strauss et al., 2006).

General Cognitive/Intellectual Ability General cognitive/intellectual ability encompasses reasoning, problem solving, and meeting cognitive demands of varying complexity. It has been identified as “the most robust predictor of occupational attainment, and corresponds more closely to job complexity than any other ability” (OIDAP, 2009, p. Intellectual disability affects functioning in three domains: conceptual (e.g., memory, language, reading, writing, math, knowledge acquisition); social (e.g., empathy, social judgment, interpersonal skills, friendship abilities); and practical (e.g., self-management in areas such as personal care, job responsibilities, money management, recreation, organizing school and work tasks) (American Psychiatric Association, 2013, p. Tests of cognitive/intellectual functioning, commonly referred to as intelligence tests, are widely accepted and used in a variety of fields, including education and neuropsychology. Prominent examples include the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale, fourth edition (WAIS-IV; Wechsler, 2008) and the Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children, fourth edition (WISC-IV; Wechsler, 2003). Language and Communication The domain of language and communication focuses on receptive and expressive language abilities, including the ability to understand spoken or written language, communicate thoughts, and follow directions (American Psychiatric Association, 2013; OIDAP, 2009).

The International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (WHO, 2001) distinguishes the two, describing language in terms of mental functioning while. Describing communication in terms of activities (the execution of tasks) and participation (involvement in a life situation). The mental functions of language include reception of language (i.e., decoding messages to obtain their meaning), expression of language (i.e., production of meaningful messages), and integrative language functions (i.e., organization of semantic and symbolic meaning, grammatical structure, and ideas for the production of messages). Abilities related to communication include receiving and producing messages (spoken, nonverbal, written, or formal sign language), carrying on a conversation (starting, sustaining, and ending a conversation with one or many people) or discussion (starting, sustaining, and ending an examination of a matter, with arguments for or against, with one or more people), and use of communication devices and techniques (telecommunications devices, writing machines) (WHO, 2001). In a survey of historical governmental and scholarly data, Ruben (1999) found that communication disorders were generally associated with higher rates of unemployment, lower social class, and lower income. A wide variety of tests are available to assess language abilities; some prominent examples include the Boston Naming Test (Kaplan et al., 2001), Controlled Oral Word Association (Benton et al., 1994a; Spreen and Strauss, 1991), the Boston Diagnostic Aphasia Examination (Goodglass and Kaplan, 1983), and for children, the Clinical Evaluation of Language Fundamentals-4 (Semel et al., 2003) or Comprehensive Assessment of Spoken Language (Carrow-Woolfolk, 1999).

There are fewer formal measures of communication per se, although there are some educational measures that do assess an individual’s ability to produce written language samples, for example, the Test of Written Language (Hammill and Larsen, 2009). Learning and Memory This domain refers to abilities to register and store new information (e.g., words, instructions, procedures) and retrieve information as needed (OIDAP, 2009; WHO, 2001). Functions of memory include “short-term and long-term memory; immediate, recent and remote memory; memory span; retrieval of memory; remembering; and functions used in recalling and learning” (WHO, 2001, p.

However, it is important to note that semantic, autobiographical, and implicit memory are generally preserved in all but the most severe forms of neurocognitive dysfunction (American Psychiatric Association, 2013; OIDAP, 2009). Impaired memory functioning can arise from a variety of internal or external factors, such as depression, stress, stroke, dementia, or traumatic brain injury (TBI), and may affect an individual’s ability to sustain work, due to a lessened ability to learn and remember instructions or work-relevant material. Examples of tests for learning and memory deficits include the Wechsler Memory.

Scale (Wechsler, 2009), Wide Range Assessment of Memory and Learning (Sheslow and Adams, 2003), California Verbal Learning Test (Delis, 1994; Delis et al., 2000), Hopkins Verbal Learning Test-Revised (Benedict et al., 1998; Brandt and Benedict, 2001), Brief Visuospatial Memory Test-Revised (Benedict, 1997), and the Rey-Osterrieth Complex Figure Test (Rey, 1941). Attention and Vigilance Attention and vigilance refers to the ability to sustain focus of attention in an environment with ordinary distractions (OIDAP, 2009). Normal functioning in this domain includes the ability to sustain, shift, divide, and share attention (WHO, 2001).

Persons with impairments in this domain may have difficulty attending to complex input, holding new information in mind, and performing mental calculations. They may also exhibit increased difficulty attending in the presence of multiple stimuli, be easily distracted by external stimuli, need more time than previously to complete normal tasks, and tend to be more error prone (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). Tests for deficits in attention and vigilance include a variety of continuous performance tests (e.g., Conners Continuous Performance Test, Test of Variables of Attention), the WAIS-IV working memory index, Digit Vigilance (Lewis, 1990), and the Paced Auditory Serial Addition Test (Gronwall, 1977). Processing Speed Processing speed refers to the amount of time it takes to respond to questions and process information, and “has been found to account for variability in how well people perform many everyday activities, including untimed tasks” (OIDAP, 2009, p. This domain reflects mental efficiency and is central to many cognitive functions (NIH, n.d.). Tests for deficits in processing speed include the WAIS-IV processing speed index and the Trail Making Test Part A (Reitan, 1992).

Executive Functioning Executive functioning is generally used as an overarching term encompassing many complex cognitive processes such as planning, prioritizing, organizing, decision making, task switching, responding to feedback and error correction, overriding habits and inhibition, and mental flexibility (American Psychiatric Association, 2013; Elliott, 2003; OIDAP, 2009). It has been described as “a product of the coordinated operation of various processes to accomplish a particular goal in a flexible manner” (Funahashi, 2001, p. Impairments in executive functioning can lead to disjointed.

And disinhibited behavior; impaired judgment, organization, planning, and decision making; and difficulty focusing on more than one task at a time (Elliott, 2003). Patients with such impairments will often have difficulty completing complex, multistage projects or resuming a task that has been interrupted (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). Because executive functioning refers to a variety of processes, it is difficult or impossible to assess executive functioning with a single measure. However, it is an important domain to consider, given the impact that impaired executive functioning can have on an individual’s ability to work (OIDAP, 2009).

Some tests that may assist in assessing executive functioning include the Trail Making Test Part B (Reitan, 1992), the Wisconsin Card Sorting Test (Heaton, 1993), and the Delis-Kaplan Executive Function System (Delis et al., 2001). Once a test has been administered, assuming it has been done so according to standardized protocol, the test-taker’s performance can be scored. In most instances, an individual’s raw score, that is the number of items on which he or she responded correctly, is translated into a standard score based on the normative data for the specific measure.

In this manner, an individual’s performance can be characterized by its position on the distribution curve of normal performances. The majority of cognitive tests have normative data from groups of people who mirror the broad demographic characteristics of the population of the United States based on census data. As a result, the normative data for most measures reflect the racial, ethnic, socioeconomic, and educational attainment of the population majorities. Unfortunately, that means that there are some individuals for whom these normative data are not clearly and specifically applicable.

This does not mean that testing should not be done with these individuals, but rather that careful consideration of normative limitations should be made in interpretation of results. Selection of appropriate measures and assessment of applicability of normative data vary depending on the purpose of the evaluation. Cognitive tests can be used to identify acquired or developmental cognitive impairment, to determine the level of functioning of an individual relative to typically functioning same-aged peers, or to assess an individual’s functional capacity for everyday tasks (Freedman and Manly, 2015). Clearly, each of these purposes could be relevant for SSA disability determinations. However, each of these instances requires different interpretation and application of normative data. When attempting to identify a change in functioning secondary to neurological injury or illness, it is most appropriate to compare an individual’s postinjury performance to his or her premorbid level of functioning. Unfortunately, it is rare that an individual has a formal assessment of his or her premorbid cognitive functioning.

Thus, comparison of the postinjury performance to demographically matched normative data provides the best comparison to assess a change in functioning (Freedman and Manly, 2015; Heaton et al., 2001; Manly and Echemendia, 2007). For example, assessment of a change in language functioning in a Spanish-speaking individual from Mexico who has sustained a stroke will be more accurate if the individual’s performance is compared to norms collected from other Spanish-speaking individuals from Mexico rather than English speakers from the United States or even Spanish-speaking individuals from Puerto Rico.

In many instances, this type of data is provided in alternative normative data sets rather than the published population-based norms provided by the test publisher. In contrast, the population-based norms are more appropriate when the purpose of the evaluation is to describe an individual’s level of functioning relative to same-aged peers (Busch, 2006; Freedman and Manly, 2015). A typical example of this would be in instances when the purpose of the evaluation is to determine an individual’s overall level of intellectual (i.e., IQ) or even academic functioning.

In this situation, it is more relevant to compare that individual’s performance to that of the broader population in which he or she is expected to function in order to quantify his or her functional capabilities. Thus, for determination of functional disability, demographically or ethnically corrected normative data are inappropriate and may actually underestimate an individual’s degree of disability (Freedman and Manly, 2015). In this situation, use of otherwise appropriate standardized and psychometrically sound performance-based or cognitive tests is appropriate. Determination of an individual’s everyday functioning or vocational capacity is perhaps the evaluation goal most relevant to the SSA disability determination process.

To make this determination, the most appropriate comparison group for any individual would be other individuals who are currently completing the expected vocational tasks without limitations or disability (Freedman and Manly, 2015). Unfortunately, there are few standardized measures of skills necessary to complete specific vocational tasks and, therefore, also no vocational-specific normative data at this time. This type of functional capacity is best measured by evaluation techniques that recreate specific vocational settings and monitor an individual’s completion of related tasks. Until such specific vocational functioning measures exist and are readily available for use in disability determinations, objective assessment of cognitive skills that are presumed to underlie specific functions will be. Necessary to quantify an individual’s functional limitations.

Despite limitations in normative data as outlined in Freedman and Manly (2015), formal psychometric assessment can be completed with individuals of various ethnic, racial, gender, educational, and functional backgrounds. However, the authors note that “limited research suggests that demographic adjustments reduce the power of cognitive test scores to predict every-day abilities” (e.g., Barrash et al., 2010; Higginson et al., 2013; Silverberg and Millis, 2009). In fact, they go on to state “the normative standard for daily functioning should not include adjustments for age, education, sex, ethnicity, or other demographic variables” (p.

Use of appropriate standardized measures by appropriately qualified evaluators as outlined in the following sections further mitigates the impact of normative limitations. Interpretation of results is more than simply reporting the raw scores an individual achieves. Interpretation requires assigning some meaning to the standardized score within the individual context of the specific test-taker. There are several methods or levels of interpretation that can be used, and a combination of all is necessary to fully consider and understand the results of any evaluation (Lezak et al., 2012). This section is meant to provide a brief overview; although a full discussion of all approaches and nuances of interpretation is beyond the scope of this report, interested readers are referred to various textbooks (e.g., Groth-Marnat, 2009; Lezak et al, 2012). Interindividual Differences The most basic level of interpretation is simply to compare an individual’s testing results with the normative data collected in the development of the measures administered. This level of interpretation allows the examiner to determine how typical or atypical an individual’s performance is in comparison to same-aged individuals within the general population.

Normative data may or may not be further specialized on the basis of race/ ethnicity, gender, and educational status. There is some degree of variability in how an individual’s score may be interpreted based on its deviation from the normative mean due to various schools of thought, all of which cannot be described in this text. One example of an interpretative approach would be that a performance within one standard deviation of the mean would be considered broadly average. Performances one to two standard deviations below the mean are considered mildly impaired, and those two or more standard deviations below the mean typically are interpreted as being at least moderately impaired. Intraindividual Differences In addition to comparing an individual’s performances to that of the normative group, it also is important to compare an individual’s pattern of performances across measures.

This type of comparison allows for identification of a pattern of strengths and weaknesses. For example, an individual’s level of intellectual functioning can be considered a benchmark to which functioning within some other domains can be compared. If all performances fall within the mildly to moderately impaired range, an interpretation of some degree of intellectual disability may be appropriate, depending on an individual’s level of adaptive functioning. It is important to note that any interpretation of an individual’s performance on a battery of tests must take into account that variability in performance across tasks is a normal occurrence (Binder et al., 2009) especially as the number of tests administered increases (Schretlen et al., 2008). However, if there is significant variability in performances across domains, then a specific pattern of impairment may be indicated. Profile Analysis When significant variability in performances across functional domains is assessed, it is necessary to consider whether or not the pattern of functioning is consistent with a known cognitive profile. That is, does the individual demonstrate a pattern of impairment that makes sense or can be reliably explained by a known neurobehavioral syndrome or neurological disorder.

For example, an adult who has sustained isolated injury to the temporal lobe of the left hemisphere would be expected to demonstrate some degree of impairment on some measures of language and verbal memory, but to demonstrate relatively intact performances on measures of visual-spatial skills. This pattern of performance reflects a cognitive profile consistent with a known neurological injury. Conversely, a claimant who demonstrates impairment on all measures after sustaining a brief concussion would be demonstrating a profile of impairment that is inconsistent with research data indicating full cognitive recovery within days in most individuals who have sustained a concussion (McCrea et al., 2002, 2003). Interpreting Poor Cognitive Test Performance Regardless of the level of interpretation, it is important for any evaluator to keep in mind that poor performance on a set of cognitive or neuropsychological measures does not always mean that an individual is truly impaired in that area of functioning. Additionally, poor performance on a. Set of cognitive or neuropsychological measures does not directly equate to functional disability. In instances of inconsistent or unexpected profiles of performance, a thorough interpretation of the psychometric data requires use of additional information.

The evaluator must consider the validity and reliability of the data acquired, such as whether or not there were errors in administration that rendered the data invalid, emotional or psychiatric factors that affected the individual’s performance, or sufficient effort put forth by the individual on all measures. To answer the latter question, administration of performance validity tests (PVTs) as part of the cognitive or neuropsychological evaluation battery can be helpful. Interpretation of PVT data must be undertaken carefully. Any PVT result can only be interpreted in an individual’s personal context, including psychological/emotional history, level of intellectual functioning, and other factors that may affect performance.

Particular attention must be paid to the limitations of the normative data available for each PVT to date. As such, a simple interindividual interpretation of PVT testing results is not acceptable or valid. Rather, consideration of intraindividual patterns of performance on various cognitive measures is an essential component of PVT interpretation. PVTs will be discussed in greater detail later in this chapter.

Qualifications for Administering Tests Given the need for the use of standardized procedures, any person administering cognitive or neuropsychological measures must be well trained in standardized administration protocols. He or she should possess the interpersonal skills necessary to build rapport with the individual being tested in order to foster cooperation and maximal effort during testing. Additionally, individuals administering testing should understand important psychometric properties, including validity and reliability, as well as factors that could emerge during testing to place either at risk (as described in ). Many doctoral-level psychologists are well trained in test administration. In general, psychologists from clinical, counseling, school, or educational graduate psychology programs receive training in psychological test administration.

However, the functional domains of emphasis in most of these programs include intellectual functioning, academic achievement, aptitude, emotional functioning, and behavioral functioning (APA, 2015). Thus, if the request for disability is based on a claim of intellectual disability or significant emotional/behavioral dysfunction, a psychologist with solid psychometric training from any of these types of graduate-level. Trained in the science of brain-behavior relationships.

The clinical neuropsychologist specializes in the application of assessment and intervention principles based on the scientific study of human behavior across the lifespan as it relates to normal and abnormal functioning of the central nervous system. (HNS, 2003) That is, a neuropsychologist is trained to evaluate functioning within specific cognitive domains that may be affected or altered by injury to or disease of the brain or central nervous system. For example, a claimant applying for disability due to enduring attention or memory dysfunction secondary to a TBI would be most appropriately evaluated by a neuropsychologist. The use of psychometrists or technicians in cognitive/neuropsychological test administration is a widely accepted standard of practice (Brandt and van Gorp, 1999).

Psychometrists are often bachelor’s- or master’s-level individuals who have received additional specialized training in standardized test administration and test scoring. They do not practice independently, but rather work under the close supervision and direction of doctoral-level clinical psychologists. Qualifications for Interpreting Test Results Interpretation of testing results requires a higher degree of clinical training than administration alone.

Most doctoral-level clinical psychologists who have been trained in psychometric test administration are also trained in test interpretation. As stated in the existing SSA (n.d.-a) documentation regarding evaluation of intellectual disability, the specialist completing psychological testing “must be currently licensed or certified in the state to administer, score, and interpret psychological tests and have the training and experience to perform the test.” However, as mentioned above, the training received by most clinical psychologists is limited to certain domains of functioning, including measures of general intellectual functioning, academic achievement, aptitude, and psychological/emotional functioning.

Again, if the request for disability is based on a claim of intellectual disability or significant emotional/behavioral dysfunction, a psychologist with solid psychometric training from any of these programs should be capable of providing appropriate interpretation of the testing. That was completed. The reason for the evaluation, or more specifically, the type of claim of impairment, may suggest a need for a specific type of qualification of the individual performing and especially interpreting the evaluation. As stated in existing SSA (n.d.-a) documentation, individuals who administer more specific cognitive or neuropsychological evaluations “must be properly trained in this area of neuroscience.” Clinical neuropsychologists, as defined above, are individuals who have been specifically trained to interpret testing results within the framework of brain-behavior relationships and who have achieved certain educational and training benchmarks as delineated by national professional organizations (AACN, 2007; NAN, 2001).

More specifically, clinical neuropsychologists have been trained to interpret more complex and comprehensive cognitive or neuropsychological batteries that could include assessment of specific cognitive functions, such as attention, processing speed, executive functioning, language, visual-spatial skills, or memory. As stated above, interpretation of data involves examining patterns of individual cognitive strengths and weaknesses within the context of the individual’s history including specific neurological injury or disease (i.e., claims on the basis of TBI). Neuropsychological tests assessing cognitive, motor, sensory, or behavioral abilities require actual performance of tasks, and they provide quantitative assessments of an individual’s functioning within and across cognitive domains. The standardization of neuropsychological tests allows for comparability across test administrations. However, interpretation of an individual’s performance presumes that the individual has put forth full and sustained effort while completing the tests; that is, accurate interpretation of neuropsychological performance can only proceed when the test-taker puts forth his or her best effort on the testing. If a test-taker is not able to give his or her best effort, for whatever reason, the test results cannot be interpreted as accurately reflecting the test-taker’s ability level. As discussed in detail in, a number of studies have examined potential for malingering when there is a financial incentive for appearing impaired, suggesting anywhere from 19 to 68 percent of SSA disability applicants may be performing below their capability on cognitive tests or inaccurately reporting their symptoms (Chafetz, 2008; Chafetz et al., 2007; Griffin et al., 1996; Mittenberg et al., 2002).

For a summary of reported base rates of “malingering,” see of this report and the ensuing discussion. However, an individual may put forth less than optimal effort due to a variety of factors other than malingering, such as pain, fatigue, medication use, and psychiatric symptomatology (Lezak et al., 2012). For these reasons, analysis of the entire cognitive profile for consistency is generally recommended. PVTs are measures that assess the extent to which an individual is providing valid responses during cognitive or neuropsychological testing. PVTs are typically simple tasks that are easier than they appear to be and on which an almost perfect performance is expected based on the fact that even individuals with severe brain injury have been found capable of good performance (Larrabee, 2012b).

On the basis of that expectation, each measure has a performance cut-off defined by an acceptable number of errors designed to keep the false-positive rate low. Performances below these cutoff points are interpreted as demonstrating invalid test performance. Types of PVTs PVTs may be designed as such and embedded within other cognitive tests, later derived from standard cognitive tests, or designed as stand-alone measures. Examples of each type of measure are discussed below. Embedded and Derived Measures Embedded and derived PVTs are similar in that a specific score or assessment of response bias is determined from an individual’s performance on an aspect of a preexisting standard cognitive measure.

The primary difference is that embedded measures consist of indices specifically created to assess validity of performance in a cognitive test, whereas derived measures typically use novel calculations of performance discrepancies rather than simply examining the pattern of performance on already established indices. The rationale for this type of PVT is that it does not require administration of any additional tasks and therefore does not result in any added time or cost. Additionally, development of these types of PVTs can allow for retrospective consideration or examination of effort in batteries in which specific stand-alone measures of effort were not administered (Solomon et al., 2010). The forced-choice condition of the California Verbal Learning Test—second edition (CVLT-II) (Delis et al., 2000) is an example of an embedded PVT. Following learning, recall, and recognition trials involving a 16-item word list, the test-taker is presented with pairs of words and asked to identify which one was on the list. More than 92 percent of the normative population, including individuals in their eighties, scored 100 percent on this test.

Scores below the published cut-off are unusually low and indicative of potential noncredible performance. Scores below chance are considered to reflect purposeful noncredible performance, in that the test-taker knew the correct answer but purposely chose the wrong answer. Reliable Digit Span, based on the Digit Span subtest of the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale, is an example of a measure that was derived based.

On research following test publication. The Digit Span subtest requires test-takers to repeat strings of digits in forward order (forward digit span), as well as in reverse order (backward digit span). To calculate Reliable Digit Span, the maximum forward and backward span are summed, and scores below the cut-off point are associated with noncredible performance (Greiffenstein et al., 1994). A full list of embedded and derived PVTs is provided in. Stand-Alone Measures A stand-alone PVT is a measure that was developed specifically to assess a test-taker’s effort or consistency of responses.

That is, although the measure may appear to assess some other cognitive function (e.g., memory), it was actually developed to be so simple that even an individual with severe impairments in that function would be able to perform adequately. Such measures may be forced choice or non-forced choice (Boone and Lu, 2007; Grote and Hook, 2007). The Test of Memory Malingering (TOMM) (Tombaugh and Tombaugh, 1996), the Word Memory Test (WMT) (Green et al., 1996), and the Rey Memory for Fifteen Items Test (RMFIT) (Rey, 1941) are examples of standalone measures of performance validity. As with many stand-alone measures, the TOMM, WMT, and RMFIT are memory tests that appear more difficult than they really are. The TOMM and WMT use a forced-choice method to identify noncredible performance in which the test-taker is asked to identify which of two stimuli was previously presented. Accuracy scores are compared to chance level performance (i.e., 50 percent correct), as well as performance by normative groups of head-injured and cognitively impaired individuals, with cut-offs set to minimize false-positive errors. Alternatively, the RMFIT uses a non-forced-choice method in which the test-taker is presented with a group of items and then asked to reproduce as many of the items as possible.

Brief Neuropsychological Cognitive Examination Pdf Editor Download

Forced-Choice PVTs As noted above, some PVTs are forced-choice measures on which performance significantly below chance has been suggested to be evidence of intentionally poor performance based on application of the binomial theorem (Larrabee, 2012a). For example, if there are two choices, it would be expected that purely random guessing would result in 50 percent of items correct. Scores deviating from 50 percent in either direction indicate nonchance-level performance.

The most probable explanation for substantially below-chance PVT scores is that the test-taker knew the correct answer but purposely selected the wrong answer. The Slick and colleagues. (Bianchini et al., 2001; Heilbronner et al., 2009). Moreover, it has become standard clinical practice to use multiple PVTs throughout an evaluation (Boone, 2009; Heilbronner et al., 2009). In general, multiple PVTs should be administered over the course of the evaluation because performance validity may wax and wane with increasing and decreasing fatigue, pain, motivation, or other factors that can influence effortful performance (Boone, 2009, 2014; Heilbronner et al., 2009).

Some of the PVT development studies have attempted to examine these factors (i.e., effect of experimentally induced pain) and found no effect on PVT performance (Etherton et al., 2005a,b). In clinical evaluations, most individuals will pass PVTs, and a small proportion will fail at the below-chance level. These clear passes can support the examiner’s interpretation of the evaluation data being valid. Clear failures, that is below-chance performances, certainly place the validity of any other data obtained in the evaluation in question. The risk of falsely identifying failure on one PVT as indicative of noncredible performance has resulted in the common practice of requiring failure on at least two PVTs to make any assumptions related to effort (Boone, 2009, 2014; Larrabee, 2014a). According to practice guidelines of NAN, performance slightly below the cut-off point on only one PVT cannot be construed to represent noncredible performance or biased responding; converging evidence from other indicators is needed to make a conclusion regarding performance bias (Bush et al., 2005).

Similarly, AACN suggests the use of multiple validity assessments, both embedded and stand-alone, when possible, noting that effort may vary during an evaluation (Heilbronner et al., 2009). However, it should be noted that in cases where a test-taker scores significantly below chance on a single forced-choice PVT, intent to deceive may be assumed and test scores deemed invalid. It is also important to note that some situations may preclude the use of multiple validity indicators. For example, when evaluating an early school-aged child, at present, the TOMM is the only empirically established PVT (Kirkwood, 2014). In such situations, “it is the clinician’s responsibility to document the reasons and explicitly note the interpretive implications” of reliance on a single PVT (Heilbronner et al., 2009).

The number of noncredible performances and the pattern of PVT failure are both considered in making a determination about whether the remainder of the neuropsychological battery can be interpreted. This consideration is particularly important in evaluations in which the test-taker’s performance on cognitive measures falls below an expected level, suggesting potential cognitive impairment.

That is, an individual’s poor performance on cognitive measures may reflect insufficient effort to perform well, as suggested by PVT performance, rather than a true impairment. However, even in the context of PVT failure, performances that are in the average range. Can be interpreted as reflecting ability that is in the average range or above, though such performances may represent an underestimate of actual level of ability. Certainly, PVT “failure” does not equate to malingering or lack of disability.

However, clear PVT failures make the validity of the remainder of the cognitive battery questionable; therefore, no definitive conclusions can be drawn regarding cognitive ability (aside from interpreting normal performances as reflecting normal cognitive ability). An individual who fails PVTs may still have other evidence of disability that can be considered in making a determination; in these cases, further information would be needed to establish the case for disability. AACN and NAN endorse the use of PVT measures in the context of any neuropsychological examination (Bush et al., 2005; Heilbronner et al., 2009). The practice standards require clinical neuropsychologists performing evaluations of cognitive functioning for diagnostic purposes to include PVTs and comment on the validity of test findings in their reports. There is no gold standard PVT, and use of multiple PVTs is recommended. A specified set of PVTs, or other cognitive measures for that matter, is not recommended due to concerns regarding test security and test-taker coaching. Caveats and Considerations in the Use of PVTs Given the primary use of cut-off scores, even within the context of forced-choice tasks, the interpretation of PVT performance is inherently different than interpretation of performance on other standardized measures of cognitive functioning owing to the nature of the scores obtained.

Unlike general cognitive measures that typically use a norm-referenced scoring paradigm assuming a normal distribution of scores, PVTs typically use a criterion-referenced scoring paradigm because of a known skewed distribution of scores (Larrabee, 2014a). That is, an individual’s performance is compared to a cut-off score set to keep false-positive rates below 10 percent for determining whether or not the individual passed or failed the task. A resulting primary critique of PVTs is that the development of the criterion or cut-off scores has not been as rigorous or systematic as is typically expected in the collection of normative data during development of a new standardized measure of cognitive functioning. In general, determination of what is an acceptable or passing performance and associated cut-off scores have been established in somewhat of a post hoc or retrospective fashion.

However, there are some embedded PVTs that have been co-normed with At the committee’s second meeting, Drs. Bianchini, Boone, and Larrabee all expressed great concern about the susceptibility of PVTs to coaching and stressed the importance of ensuring test security, as disclosure of test materials adversely.

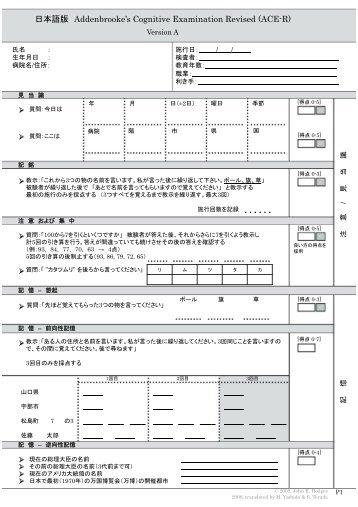

This convenient test assesses the cognitive functions targeted in a typical neuropsychological exam. In less than 30 minutes, it gives you a general cognitive profile that can be used for screening, diagnosis, or follow-up. More efficient than a neuropsychological battery and more thorough than a screener, BNCE is an ideal way to evaluate the cognitive status of patients with psychiatric disorders or psychiatric manifestations of neurological diseases. Authors: Joseph M. Tonkonogy, M.D., Ph.D.

Publishers: PsychCorp Available in South Africa from: Mindmuzik Media Tel: 012 342 1606 Fax: 012 342 2728 E-mail: sales@mindmuzik.com Website: www.mindmuzik.com.